Over 55 million children in the U.S. were sent home to complete the last three months of the 2019-2020 school year via distance learning due to the COVID-19 pandemic. This sudden change to schooling across the country disrupted the educational system and shed new light on long-existing inequities. As districts, teachers, families, and youth were suddenly tasked with planning and implementing at-home learning, inequitable access to technology, commonly called the digital divide, was quickly at the forefront. Research shows the digital divide is not just in access to equipment but also technology self-efficacy, indicating that youth with varied access likely navigate remote learning experiences with different levels of confidence, a key enabler to learning(1). Recent studies indicate many districts anticipate continuing remote learning beyond the pandemic, with RAND reporting 20% of districts “have adopted, plan to adopt, or are considering adopting virtual school as part of their district portfolio” based on families and students’ requests for more online learning(2). This likely continuation of remote learning makes a focus on technology self-efficacy, confidence, and opportunities to engage even more critical.

2020 Hindsight

At the start of the 2020 school year, The U.S. Census Bureau found 4.4 million households with children lack regular access to a computer for educational purposes, and 3.7 million households do not consistently have internet available for educational purposes. The National Center for Education Statistics (NCES) found barriers to computer and internet access disproportionally affects youth from low-income households, rural school districts, and youth who identify as Black, Hispanic, and American Indian and Alaskan Native(3). In high-poverty schools, less than one-third (30%) of teachers said all or nearly all of their students had access to home internet(4).

Researchers found that beyond materials, there are also motivational, skill, and usage pattern differences based on exposure to technology. Students are more likely to experience low self-efficacy and high anxiety when using technology, particularly when there is a persistent lack of access(1). Because self-efficacy is a critical component for learning, the digital divide is important to consider when reviewing the effects of the COVID-related shifts to remote learning. It is likely that many students, on their first day of remote learning, experienced low self-efficacy, not necessarily in the content itself, but in using the technology they needed to engage in it.

How BellXcel Remote Met the Moment

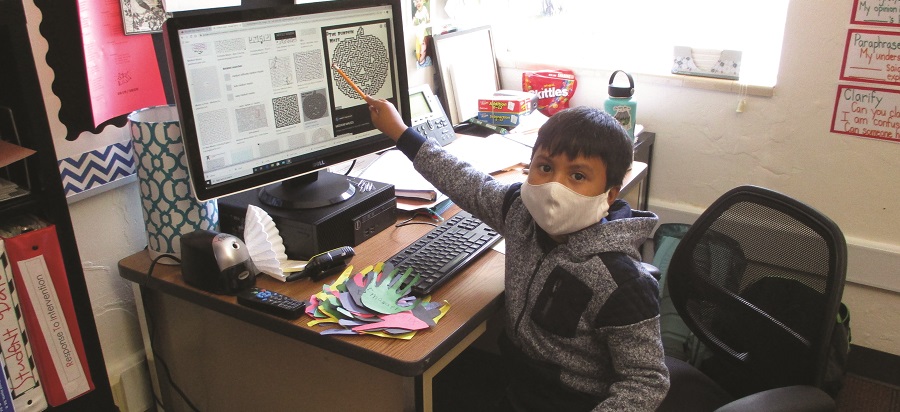

While school staff, families, and youth made real-time adaptations to learn at home, BellXcel was also innovating. BellXcel is a national non-profit that offers evidence-based products and services for youth organizations and schools. The learning model was intentionally designed as a product, called BellXcel Remote, to meet the needs of all families, including those with limited to no technology in the home. In a December 2020 research brief called Building Bridges During Challenging Times: How BellXcel Remote Summer Programs Kept Youth, Families and Staff Engaged in Learning During COVID-19, The Sperling Center for Research and Innovation (SCRI) reviewed how BellXcel Remote provided opportunities for engagement in learning, and how effective those opportunities were. The findings indicated that by designing the BellXcel Remote model to align with best practices in out-of-school time (OST), partner programs across the country successfully built and maintained youth, family, and staff engagement throughout the summer.

Through a qualitative review of post-program stakeholder surveys, SCRI also uncovered an unexpected effect of participating in a summer program: Families, staff, and youth reported that participating in the summer program increased confidence in remote learning and technology, improving preparedness for potential shifts and uncertainties in the school year, and in some cases repairing negative perceptions of remote learning from the spring of 2020.

This brief explores this theme and looks to uncover why the experience of BellXcel Remote resulted in these findings.

Sources:

- Huang, K. T., Ball, C., Cotten, S. R., & O’Neal, L. (2020). Effective experiences: A social cognitive analysis of young students’ technology self-efficacy and STEM attitudes. Social Inclusion, 8(2), 213-221.

- Schwartz, H., Grant. D., Diliberti, M., Hunter, G., and Messan Setodji, C. (2020). Remote learning is here to stay: Results from the first American School District Panel survey. RAND Corporation. https://www.rand.org/pubs/research_reports/RRA956-1.html

- USAFacts. (2020, October 19). More than 9 million children lack internet access at home for online learning. Retrieved December 14, 2020, from https://usafacts.org/articles/internet-access-students-at-home/

- Stelitano, L., Doan, S., Woo, A., Diliberti, M., Kaufman, J., Henry, D. (2020). The digital divide and COVID-19: Teachers’ perceptions of inequities in students’ internet access and participation in remote learning. RAND Corporation. https://www.rand.org/pubs/research_reports/RRA134-3.html